Discovery of a Pre-Inca Culture#

El Purgatorio Alto Near Casma, Peru#

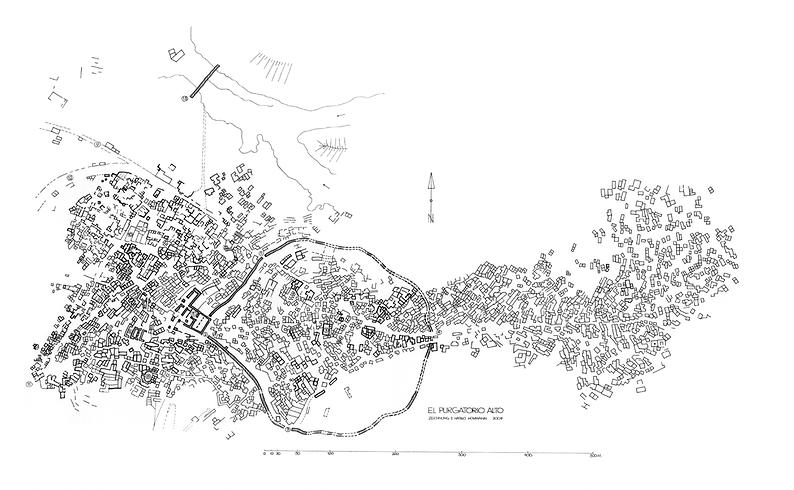

On my trip in the summer of 1996, I also visited Peru. One of my destinations was the archaeological site of El Purgatorio near Casma Peru, Casma . Casma is a growing coastal city at a distance of about 320 km to the northwest of Lima in the Ancash region. El Purgatorio lies about 11.5 km to the southeast of Casma in the extremely dry coastal desert between the Cordillera and the Pacific Ocean. The archaeological site has an extension of about 600 m by 600 m and consists of the remains of huge administrative centres from the Wari period (about 700 to 1200 AD).

As early as in 2002, an illegal settlement was put up directly to the west of these ruins, its football ground was on a leveled field of the archaeological site in the south. In the archaeological area you can also see a burial ground at the foot of the ascent to a steep hill in the south of the complex. Here, a path leads up to a chapel with a good view. From here you can also make out several small funnel-shaped depressions at the foot of the hill. The field looks like after a bombing. The funnels are the marks of looters who have opened the graves. Presumably the inhabitants of the nearby village have searched for valuable objects.

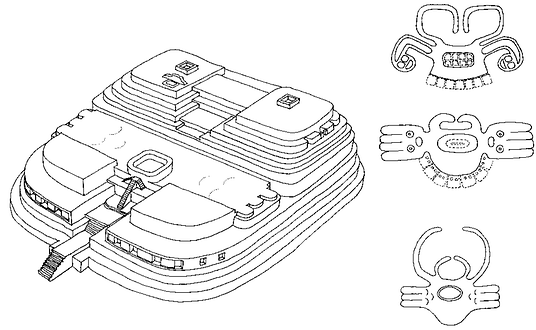

The ruins consist of several elongated rectangular hills of debris. Those are the remains of buildings and of differently sized courtyards. In some of these courtyards, secondary smaller and more compartmentalized components can be seen. All this has not yet or hardly been investigated archaeologically and also shows no details.

I therefore looked at the complex again in 2008, but at home in Graz and on Google Earth. From a great height you can often make out much better the rectangularly designed buildings and courtyards as well as the routing. It probably was a methodically structured palace and temple complex from the Wari period. The buildings have probably been destroyed by weather and heavy earth earthquakes. This seems conclusive based on the uniformity of the scene of destruction.

After studying the archaeological site, I somewhat by chance swiveled on Google Earth a little bit to the east to the massif of the extinct and heavily eroded volcano Cerro Mucho Malo. Here I saw, in a roughly 100 m horizontal distance to the ruins of El Purgatorio on an elevated terrain, the adjoining groundplan shapes of many buildings of an undiscovered, at least unpublished, pre-Columbian city - not appearing in any map until that day. Such a thing is of course really exiting. Maybe, after a very long time you may be the first to look again at the streets, the small squares, a central little plaza of a long abandoned city. The approximately round centre of the city is surrounded by a massive wall of about 6 m. Next to one of the passages in the defensive wall, one can see a building with an exterior wall, several metres thick, probably a temple.

Drawing: Hasso Hohmann 2008, under CC BY-SA 4.0

The area with the residential houses comprises a small erosion valley which was protected against the draining of water at its lower end by a weir. After rainfall, the dam wall also helped to hold back water for the city, but mainly it probably served as a protection for the large courtyard complexes of El Purgatorio adjoining below. I called the site, newly-found on Google Earth, due to its geographical and temporal proximity 'El Purgatorio Alto'.

In 2009, I visited Peru for the sixth time. Because of my find 'al desko' Adele and I also went to the Casma area again. We had booked into a small hotel in the city. By that time, small and manoeuvrable three-wheeled mopeds, imported from Asia, were used as taxis. They are also referred to as "Tucktuck" and have the seat for the driver in the front and a short bench for two customers in the rear. Already around 6.00 clock we set off equipped with camera, rolls of film, compass, measuring tape, water bottle, some provisions and the printouts of the Google Earth aerial photos.

The maneuverable Tuck-tuck managed through the narrowest passages and curves of the approximately 18 km stretch of road through the desert and the adjacent river oasis. First, it brought us to the ruins of Pampa de Llamas and some adjacent ruins. Afterwards, it drove us quite quickly to the foot of Cerro Mucho Malo. I paid the agreed-upon price and we said goodbye to the driver. From here we first went up to the chapel overlooking El Purgatorio and many other ruins: the Pyramid of Moxeke, the huge palace of Pampa de Llamas, the observatorio with its 13 towers and Castillo Chankillo on the other side of the Casma Valley. Most of these buildings are located in a zone completely bare of vegetation.

Drawing: Hasso Hohmann 2008., under CC BY-SA 4.0

Photo: Hasso Hohmann 2009, under CC BY-SA 4.0

Afterwards I hoped to get at the same height to the city I had discovered in Graz. Unfortunately, there was yet another valley before getting to the volcanic cone, so we had to walk down once again to the level of El Purgatorio. Maybe it is a passage or a shortcut of the largely straight-ligned, at the beginning at least about 55 m wide processional way starting on the coast at Las Haldas and leading about 22 km to the Moxeke complex and El Purgatorio.

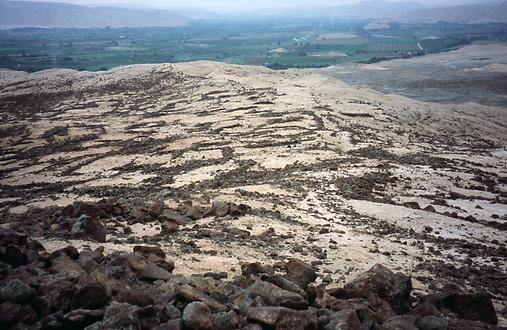

On the other side of the valley, the path ascended steeply again. After this ascent followed a rolling, relatively flat area on the mountainside of the Cerro. It is marked by a pale, fine-grained soil material with loose dark volcanic stones on top. At first I could not determine any groundplans. It took me some time to orient myself by a straight-lined road at the northern end of the southern urban zone which I could also identify on the prints. I was in El Purgatorio Alto.

Photo: Hasso Hohmann 2009, under CC BY-SA 4.0

Photo: Hasso Hohmann 2009, under CC BY-SA 4.0

Now I was able to search specifically for the adjacent layout which became clearly visible by the stone remains. So I knew exactly where in the complex I was standing. The difficulty of orienting myself in the beginning explains why, despite the many archaeologists who have been visiting this area since the beginning of the 20th century, the city above El Purgatorio had not yet been discovered. You need an aerial photo.

The black volcanic rocks lying roughly in line are obviously only the rain-proof foundation strips of the former houses. The mud walls on top have long since been swept away by the few, but heavy rains of this coastal desert over the past 800 or more years. But the stones of the foundation strips have remained. Due to their weight they have not changed their position on the slightly sloping or terraced terrain. Once they prevented the rise of moisture in the mud masonry and were resistant to running surface water in the open space around the houses. The tracing of the groundplans in Graz revealed about 2000 houses. Thus, the former town could have had 10,000 inhabitants!

However, I had to realize that I was not the discoverer of the archaeological site, because in and around the buildings graves already had been ransacked. Probably hunters had repeatedly come across graves which had become exposed by pluvial erosion on the steep slopes. Ceramic finds suggest its earliest settlement around 400 AD and the final abandonment of the city around 1200 AD.

After visiting the city, its ramparts, the temple and the dam wall in the valley between the two halves of the city, after a few drawings and photos and the study of the pottery for age determination, we set out to the southeast to visit the foundations of a palace at the foot of the Cerro. Then we crossed the Casma Valley and first visited the north-south-oriented granite hill with its 13 towers, each with a staircase. The towers are interpreted as an observatory. Their walls have impressive dimension and, considering their age of almost 3000 years, they are still relatively well preserved. Whether it really was an observatory has to be finally solved at some stage. The northern nine of the 13 towers were built in a straight line in north-south direction, but the southern four towers lead westwards in a distinct arc. The 12 spaces between the towers might have been used as an observatory from the west.

Afterwards we went up a steep slope to the Castillo Chankillo which I had already visited one night in 1996 in a flying visit. Back then I had also taken pictures of the 13 towers of the observatory from above.

The way up leads over very old coarse-grained granite rocks, whose large crystals dissolve easily on the surface resulting in a kind of coarse sand, on which one slips like on loose gravel. Several times I had to help Adele. But this time I had more time in the Castillo and could examine several of the gates and gauge the construction of the defensive walls as well as other details.

Photo: Hasso Hohmann 2009, under CC BY-SA 4.0

Photo: Hasso Hohmann 2009, under CC BY-SA 4.0

Photo: Hasso Hohmann 2009, under CC BY-SA 4.0

The sun was already low on the horizon when we left the fortress to reach the Panamericana more than three kilometers away. In the background we saw the Señal Mongon veiled in clouds. It is 1144 m high and stands directly on the coast. In 2004, I had climbed the mountain, an old volcano, when I tried to test my condition after two hospital stays with operations. At the same time I had wanted to see if a report from the 19th century about an oasis on the mountain in the clouds was true. The mountain is almost always veiled in clouds. Oasis I found none.

Soon we heard vehicles on the Panamericana, the main connection between the north and the south of the country and also of all South America. When we reached the two-lane asphalt road, it was already dark and a very friendly Peruvian took us with him the 17 km to Casma. There we went to a restaurant and ordered a delicious vegetable soup with lots of vegetables and rice. Along with it we drank aniseed tea.