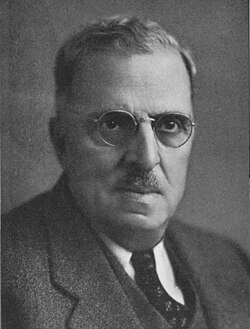

Arturo Castiglioni

Arturo Castiglioni (* 10. April 1874 in Triest, Österreich-Ungarn; † 21. Januar 1953 in Mailand) war ein italienisch-US-amerikanischer Arzt und Medizinhistoriker.

Leben und Wirken

Als Sohn des Mathematiklehrers und späteren Rabbiners Vittorio Castiglioni (1840–1911) und seiner Ehefrau Enrichetta Bolaffio wurde Arturo Castiglioni am 10. April 1874 in Triest geboren, sein Bruder war der Unternehmer Camillo Castiglioni. In Triest besuchte er auch die Schulen. Nach Erlangung der Hochschulreife humanistischer Fachrichtung studierte er von 1892 bis 1896 Medizin an der Universität Wien. Seine Studienzeit fiel in die Hochblüte der Zweiten Wiener Medizinischen Schule. Er konnte so Vorlesungen bei Wissenschaftlern internationaler Bedeutung besuchen: Siegmund Exner-Ewarten (Physiologie), Salomon Stricker (experimentelle Pathologie), Emil Zuckerkandl (Anatomie), Richard Paltauf und Anton Weichselbaum (Pathologie), Hermann Nothnagel (Klinik Innere Medizin), Theodor Billroth (Chirurgie), Richard von Krafft-Ebing und Julius Wagner-Jauregg (Psychiatrie). Die Wiener Medizinische Schule war auf dem Höhepunkt ihres Konfliktes mit Freud. Seit 1888 war Theodor Puschmann Ordinarius für Medizingeschichte in Wien ohne eigenes Institut. Zu den wenigen Hörern in Puschmanns Vorlesungen gehörten neben Castiglioni auch Isidor Fischer und Max Neuburger, der später Inhaber des Wiener Lehrstuhls wurde.[1]

Von 1896 bis 1898 arbeitete Castiglioni zwei Jahre lang als Assistent in der Wiener Medizinischen Klinik auf der Abteilung von Leopold Schrötter von Kristelli. Anschließend kehrte er nach Triest zurück, wo er von 1898 bis 1904 als Assistenzarzt im Städtischen Krankenhaus arbeitete. Von 1899 bis 1918 war er leitender Arzt des Österreichischen Lloyds und von 1918 bis 1938 des Lloyd Triestino und der Italian Line.

1921 war er Privatdozent für Geschichte der Medizin an der Universität Siena, von 1922 bis 1938 Professor für Geschichte der Medizin an der Universität Padua.

Mit antisemitischer Begründung wurde Castiglioni seiner Funktionen an der Universität Padua enthoben. Im September 1938 verweigerten ihm die italienischen Behörden ein Ausreisevisum zur Teilnahme am 11. Internationalen Kongress für Geschichte der Medizin in Jugoslawien.[2] Im November 1939 wanderte er in die USA aus. An der Yale University wurde er «Research Associate» und Dozent, 1943 Professor für Geschichte der Medizin. 1942 wählte die «New York Society for Medical History» ihn zu ihrem Präsidenten. 1946 erlangte er die amerikanische Staatsbürgerschaft, kehrte aber im Sommer 1947 nach Europa zurück, nicht in seine Heimatstadt Triest, sondern nach Mailand. Die erzwungene Emigration in fortgeschrittenem Alter hatte tiefe Narben bei den Eheleuten Castiglioni hinterlassen.[3]

Henry E. Sigerist: Epistola dedicatoria. Presented to Professor Arturo Castiglioni on the occasion of his seventieth birthday:

|

|

Weitere Aktivitäten im Bereich der Medizin und Medizingeschichte:

- 1922 bis 1929 Mitglied im Hohen Rat für öffentliche Gesundheitspflege in Rom

- 1924 bis 1938 Professor für Geschichte der Wissenschaften an der Ausländeruniversität Perugia

- 1930 Dozent für Medizingeschichte an den Universitäten São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires und Santiago de Chile

- 1933 Hideyo-Noguchi-Dozent an der Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore

- 1933 Vorlesungen über Medizingeschichte an Universitäten und vor medizinischen Gesellschaften an verschiedenen Orten der USA.

- 1934 Vorlesung an der Royal Society of Medicine in London

Veröffentlichungen (Auswahl)

- La vita e l’opera di Santorio Capodistriano. 1920

- Emile Recht (Übersetzer). The life and work of Santorio Santorio (1561–1636). Medical life press, New York 1932

- Medici e medicine a Trieste al principio dell’Ottocento. G. Balestra, Triest 1922

- Il volto di Ippocrate. Istorie di medici e medicine d’altri tempi. Soc. Ed. Unitas, Mailand 1925

- Storia della medicina. Soc. Ed. Unitas, Mailand 1927.

- 2. Ausgabe 1933; 3. überarbeitete Ausgabe 1936

- J. Bertrand und F. Gidon (Übersetzer). Histoire de la médecine. Payot, Paris 1931

- G. Stiassny (Übersetzer). Geschichte der Medizin. Weidmann Medizinischer Verlag, Wien und Leipzig 1938

- E. Capdevilla y Casas (Übersetzer). Historia de la medicina. Salvat Editiones, Barcelona und Buenos Aires 1941

- E. B. Krumbhaar (Hrsg. und Übersetzer): A History of Medicine. A. Knopf, New York 1941.

- Die italienischen Lehrer und Ärzte an der Wiener Medizinischen Schule. In: Festschrift für Max Neuburger. Wien 1928

- Storia della tuberculosis. In: Trattato italiano delle tuberculosis. Band 1, Vallardi, Mailand 1931

- History of tuberculosis. Froben Press, New York 1933

- The Renaissance of Medicine in Italy. Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore 1933

- L’orto della sanitá. Librerie Italiane Riunite, Bologna 1935 (Digitalisat)

- Aulus Cornelius Celsus as a Historian of Medicine. (Transactions of the Sixteenth Annual Meeting of the American Association of the History of Medicine. The Fielding H. Garrison Lecture.) In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine Band 8 (1940), S. 587 ff.

- Galileo Galilei and his influence on the evolution of medical thought. In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine Band 12 (1942), No 2

- The origin of the University of Vienna and the rise of the Medical School. In: Ciba Symposia. Juni–Juli 1947 (Digitalisat)

- Gerolamo Fracastoro e la dottrina del contagium vivum. In: Gesnerus Band 8 (1951), S. 52–65 (Digitalisat)

- Der Aderlass. In: Ciba-Zeitschrift. Band 66, Nr. 6, Wehr / Baden 1954, S. 2186–2216.

Literatur

- Henry E. Sigerist: Epistola dedicatoria, Vita und ausführliche Bibliographie. In: Essays in the History of Medicine. Presented to Professor Arturo Castiglioni on the occasion of his seventieth birthday (= Supplements of the Bulletin of the History of Medicine Nr. 3). Baltimore 1944, S. 1–15

- Henry S. Sigerist: Arturo Castiglioni. In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine Band 27 (1953), S. 387–389

- John Farquhar Fulton: Arturo Castiglioni. In: Journal of the History of Medicine Band 8 (1953), S. 129–132

- Hans Fischer: Arturo Castiglioni. In: Gesnerus Band 11 (1954), S. 53–54 (Digitalisat)

Weblinks

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ Michael Hubenstorf. Eine “Wiener Schule” der Medizingeschichte? – Max Neuburger und die vergessene deutschsprachige Medizingeschichte. In: Medizingeschichte und Gesellschaftskritik. Festschrift für Gerhard Baader. Matthiesen, Husum 1997, S. 246–289, hier: S. 286–287.

- ↑ Henry E. Sigerist. Yugoslavia and the XI-th International Congress of the History of Medicine. In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine Band 7 (1939), S. 108.

- ↑ Henry E. Sigerist: Epistola dedicatoria. In: Essays in the History of Medicine. Presented to Professor Arturo Castiglioni on the occasion of his seventieth birthday (= Supplements of the Bulletin of the History of Medicine Nr. 3). Baltimore 1944, S. 1–7; Henry E. Sigerist: Arturo Castiglioni. In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine Band 27, 1953, S. 387–389.

- ↑ Henry E. Sigerist: Epistola dedicatoria. In: Essays in the History of Medicine. Presented to Professor Arturo Castiglioni on the occasion of his seventieth birthday (= Supplements of the Bulletin of the History of Medicine Nr. 3), Baltimore 1944, S. 2.

| Personendaten | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Castiglioni, Arturo |

| KURZBESCHREIBUNG | italienischer Arzt und Medizinhistoriker |

| GEBURTSDATUM | 10. April 1874 |

| GEBURTSORT | Triest |

| STERBEDATUM | 21. Januar 1953 |

| STERBEORT | Mailand |

License Information of Images on page#

| Image Description | Credit | Artist | License Name | File |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arturo Castiglioni | https://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/image/L0015201.html | Atelier Margit | Datei:Arturo Castiglioni.jpg | |

| Arturo Castiglioni im Alter | Journal of the History of Medicine | Autor/-in unbekannt Unknown author | Datei:Arturo Castiglioni Altersbid.jpg | |

| The Wikimedia Commons logo, SVG version. | Original created by Reidab ( PNG version ) SVG version was created by Grunt and cleaned up by 3247 . Re-creation with SVG geometry features by Pumbaa , using a proper partial circle and SVG geometry features. (Former versions used to be slightly warped.) | Reidab , Grunt , 3247 , Pumbaa | Datei:Commons-logo.svg |